In recent years, the media union BECTU has been making progress in gaining recognition within the cinema sector and negotiating pay rises and stable contracts for cinema workers. The successes have been due to a mixture of campaigning, industrial action and use of the recognition process. As we will see, these often overlap and work side by side. Exploiting and attacking the self-proclaimed ‘ethical’ or ‘independent’ values of the brands of companies within which the union is organising has been a successful tactic.[1] In this essay I will explore the effectiveness and pitfalls of trade union recognition through two examples: the Curzon workers’ success in gaining recognition and winning the Living Wage and the failure of Picturehouse workers to gain recognition at Clapham Picturehouse, coming out of a formidable struggle at the Ritzy cinema (which is also part of the Picturehouse chain).

Trade union recognition in a workplace ensures that the trade union is a an official and visible body representing a body of workers in industrial matters. TULR(C)A 1992 and the Employment Relations Act 1999 set out collective bargaining[2] as the main function of trade union recognition[3]. To qualify for recognition, a trade union must be constituted according to and fulfil the functions as set out in the same Act. It also has to be recognised as independent by the Certification Officer. There are substantial tests which the CO uses to determine independent status, some of which include the union’s independence from employer, proof of shop stewards setting the agenda, determining how easily the employer can curtail independence, its negotiating record, finances, membership base and history. In addition, there is a £3000 charge. Once certified, this enables a trade union’s unique status as a quasi-corporate body[4] and provides immunities from common law prosecution for criminal conspiracy or restraint of trade[5]. These aspects and functions, even though they are detailed by statute, can be interpreted in different ways by the Central Arbitration Committee (CAC), as we shall see below. Before we turn to our two cases, it is worth situating them in a brief chronology which immediately demonstrates the dynamic relationship between these two struggles and within those in the cinema sector:

2013

April Curzon workers start public campaign for recognition in 10 cinemas across the country and for the Living Wage (LW)[6]

August Formal request for voluntary recognition at Curzon made by BECTU; within a week management announces a pay rise; the workers decide to pursue the application; pay negotiations start at the Ritzy cinema (run by Picturehouse Cinemas but owned by Cineworld since December 2012), the workers asking for the LW

October Formal application to CAC made for statutory recognition at Curzon World

November Curzon accepts ‘in principle’ voluntary recognition of BECTU[7]

December CAC accepts BECTU application for recognition at Curzon World[8]

2014

January Method of collective negotiation agreed and signed between BECTU and Curzon World, BECTU withdraws the application for statutory recognition

March Pay negotiations break down and strikes start at Ritzy cinema

July A boycott of Picturehouse Cinemas starts called by BECTU and supported by the TUC; a Cinema Workers rally held in London which sees workers from across the nation gathering in London to campaign for the LW and to raise the profile of trade unionism in the cinema sector[9]

September After 13 strikes, Ritzy workers negotiate a pay deal which falls short of the living wage

October Picturehouse management announces redundancies as the cost of negotiated increased wages at the Ritzy; a day later, Curzon management promises to pay LW; Picturehouse withdraw the redundancies[10]

December BECTU applies for recognition at Clapham Picturehouse

2015

February Central Arbitration Committee decides that the Staff Forum is already a recognised trade union at Clapham Picturehouse and refuses BECTU’s recognition application

In the case of Curzon, a group of workers new to trade unionism had to learn the mechanics of collective bargaining and the first hurdle was gaining recognition. Instead of blindly pursuing the statutory process, they focussed on making their demands known to the wider public and petitioning the Curzon patrons in order to pressure management into voluntary recognition. After 6 months of campaigning, BECTU submitted a claim for statutory recognition. As BECTU National Official, Sofie Mason told me in an interview:

‘Holding the company to account through the legally enforceable and detailed procedures required by the CAC was part of the jigsaw of pressures brought to bear on Curzon to do the right thing. The online petition signed by 7,000+, the celebrity names expressing opinions loudly in public, the comedy stunts by Mark Thomas, the chance that staff might follow the Ritzy example and go on strike and the one producer who pulled his film, were all critical.’

Crucial to this pressure was the workers’ capture of the Curzon brand through a campaign for restoring concessionary ticket prices for the disabled, senior citizens, students and the unemployed. The workers were therefore able to argue the Curzon patrons’ case, the business case and their own interchangeably.

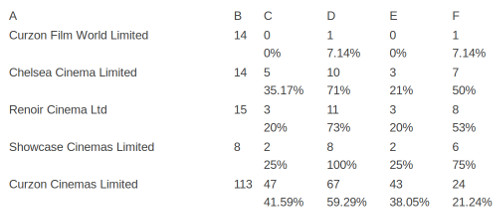

It is useful to have a look at the breakdown of the petition in favour of union recognition submitted as part of the statutory process (see Appendix A). It is clear from column D that the number of petition signatories is well over 50% in most of the different cinema branches and that the 108 signatories form 66% of the total workforce (164) – a sufficient indication that the turn-out of 40% required for the statutory ballot would have been met and that the support for recognition would have been demonstrated. However, it is worth bearing in mind that the drop-off rate is an unknown quantity, especially since the percentage of all union members was a mere 35%. In addition, the management tried to undermine the case for recognition by giving all staff a pay rise in August 2013. A third risk of high staff turnover is outlined by Sofie Mason: ‘The CAC process is a lengthy one that can last for months – with a high turnover of staff, the reps needed to work very hard to keep up the levels of membership and the level of interest in voting in the long-awaited ballot.’ This is an added hurdle to organising in unstable industries where workers are precariously employed or underemployed on zero hour contracts and one which works against trade unionists pursuing statutory recognition.

The Curzon workers’ campaign between April 2013 and January 2014 won them recognition, but it was the threat of an uprising in the wider cinema sector which led to them winning the living wage. The Cinema Workers’ Demo in July 2014 and the many months of the persistent Ritzy strikes which often took to visiting other cinemas and cinema chains were sufficient to demonstrate to the Curzon management that the brand damage and actual cost of paying the living wage were less than a direct confrontation with the workers who had already captured their brand. What this shows clearly is that it is not the strength of one branch or the weakness of one employer, but the efficacy of a trade union (or sister unions) within the industry and the sector more widely, which determine the outcomes of struggles for recognition and wages. Also, that chances of success are increased if the industrial and legal struggles run side by side.

We now turn to the Clapham Picturehouse case, which forms part of the cinema workers’ struggle for recognition in the entire Picturehouse chain. It is worth bearing in mind the chronology of struggle in the cinema industry between April 2013 and December 2014 when BECTU submitted the forms for statutory recognition. During this time, Picturehouse management vigorously attempted to neutralise the BECTU Ritzy branch in different ways and break the strike, all of which failed and the workers won a 26% pay rise in September 2014. Also relevant for our considerations is the previous CAC judgement BECTU & City Screen Limited from 2003[11]. The spouse of the then Labour PM, Cherie Booth QC represented City Screen Ltd in their attempt to put forward the City Screen Staff Forum as a recognised trade union which would invalidate BECTU’s application under Para35 of Schedule A1 of TULR(C)A 1992. The Forum was established only 4 days after BECTU’s application was made to CAC and it was composed of managerial staff exclusively. It was disqualified as a trade union, even though it had a listing with the Certification Officer. The CAC was of the opinion that the recognition agreement was signed by the company with itself (rather than two parties) and without any involvement of the staff affected. The aspirations of the Staff Forum to gain members and engage in collective bargaining were thrown out. 11 years later, in their application to CAC for recognition at Clapham Picturehouse, BECTU detailed an impressive list of objections to considering City Screen Staff Forum[12] as an existing, recognised trade union. What follows is a brief summary.

The Forum’s annual return showed no income or expenditure. Members did not pay subscriptions, which led BECTU to claim that these were not members in the sense commonly understood by trade unions. Like in 2003, one of two Forum officers remained a senior manager. The Forum is not an ‘organisation of workers’ as defined in section 1 of TULR(C)A 1992: its head office is in the premises of the Company. It had displayed no evidence of collective bargaining – pay offers were revised but did not demonstrate any negotiation. Communication with members is not what would be expected of a trade union: no motions were presented, there was no debate, no voting or discussion of policy, minutes showed no evidence of collective bargaining. The Forum was in breach of its own rules: of two trustees, none were appointed; the next AGM was scheduled for 2015, which is much later than stipulated (in addition, the CAC noted that none of the previous AGMs of the Forum were quorate). If it is a trade union, BECTU asked, why does the Forum rule book say “the name of the forum” rather than “the name of the union”? It was set up without consultation with the workforce and the Managing Director signed the agreement on behalf of the Forum in 2003. It does not offer legal services, does not have an executive committee, it had not threatened strike action or requested for dispute to be sent to ACAS, (as per the 2003 judgement) it has no collective agreement in force which qualifies under para 35 of the schedule. It is ultimately not independent and therefore subject to influence/control by the employer. The Demir[13] judgement at ECHR was invoked to underline that sham agreements with sham unions should be disregarded.[14]

The Employer’s response was equally detailed. They stated the Forum incurs no cost because it meets at the employers’ premises and Picturehouse provided facilities free of charge as well as paid time off for Forum representatives. The Forum was handed over to members in March 2004 when elections for officials took place even though it was established without their involvement. It has 174 members across 19 sites, each having a Forum Site Rep. The Forum Administrator is now a senior employee but is a duly elected official of the Forum on its behalf. Mr Allenby, even though a senior manager and Forum officer would lead members on strike if needed – there is no conflict of interest.[15] It is not a sham union since it negotiated a 10% pay increase in 2014 and a further 2% three months later. Membership is open to all – one is not automatically a member, every staff member can stand in the elections, attend and vote at general meetings or in ballots. Proof of collective bargaining was offered in the form of initial and final pay offers. Picturehouse representatives stated that 2014 negotiations ‘became tense’ with three attempts to reach agreement that year, but the minutes do not expand on this. They were likewise unaware of how the Forum consulted members but believed they voted, perhaps by email. They stated The Forum was bound by its rules, even if unaware of them (as per John v Rees [1970] Ch 345). They also underlined that there is a collective agreement on pay, hours and holidays signed on 9 January 2004. They stressed that circumstances from 2003 no longer apply: the Forum has a substantial number of members, it consists wholly or mainly of workers as described in the Recognition Agreement, has undertaken functions of trade union and the absence of serious conflict between the Forum and employer indicates the success of the collective bargaining process. It was able to show that it represented members at disciplinaries and grievances (with positive outcomes), participated in communications meetings and pay negotiations; held meetings in relations to pay negotiation. They conceded that Forum reps (even though self-selected) had no formal process by which they provided credentials to employer. However, they ultimately conceded that the Forum was not independent when they stated that

‘…the broad definition of a trade union at section 1 of the Act assumed an organisation was a trade union even if it was thus dominated and controlled, although such an organisation would not be able to obtain a certificate of independence.’[16]

Finally, responding to claims from BECTU which drew on the wider campaign and compared terms and conditions at the Ritzy and Clapham cinemas, they stated that they were ‘different’, rather than better at the Ritzy: through bonuses, there was potential to earn more at Clapham. They also resolutely stated that the fact that BECTU campaigned at Clapham in the summer of 2014 had no influence on the 2015 pay negotiations.

The CAC considered both sets of arguments and looked at three areas in determining the Forum’s validity and BECTU’s application: has there been a change of circumstance since 2003, is there a collective agreement in force and does the Demir judgement affect how a domestic body would determine the Forum’s validity? The CAC conceded that the Forum ‘is highly atypical as an organisation, let alone an organisation of workers.’[17]However, once it became an organisation with members and elected officials in March 2004, it de facto became a trade union which had

‘the minimum sufficient structure and agreed processes to represent, to some extent, the interest of its membership with non-managerial cinema staff and is seeking to do this.’[18]

The CAC determined it was different from a consultative body (since it meets the minimum requirements in section 1 of the Act) and is currently operating as

‘an organisation (whether temporary or permanent) (a) which consists wholly or mainly of workers of one of more descriptions and whose principal purposes includes the regulation of relations between workers of that description… and employers.’[19]

It was therefore to be treated as a trade union, even though not an independent one. The fact that the Forum administrator is a senior manager compromised its standing, but not fatally. The CAC accepted that the evidence provided showed that collective bargaining as defined under s178 of TUL(C)RA 1992 had taken place. The 2014 pay talks and negotiations between Forum and Employer, related to or were connected to ‘the terms and conditions of employment, or the physical conditions in which any workers are required to work’.

Turning to the Demir judgement and BECTU’s claim that in order to give effect to article 11 (freedom of assembly and association) the reference in paragraph 35[20] should interpret ‘a union’ as ‘an independent union’, the CAC was not persuaded. Furthermore, it stated that it must comply with the Boots[21] judgement which came after Demir and determined that there is no incompatibility between Article 11 of ECHR and schedule 35, since the collective agreement is terminable by the process in Part VI (Derecognition where union not independent) of TULR(C)A 1992. [22]

The CAC’s acceptance of the City Screen Staff Forum as a trade union sets a dangerous and damaging precedent for industrial organising. By interpreting the law so narrowly, it is arguably following the letter, but not the spirit of the law. It was also able to remain consistent with its previous judgement from 2003, because Picturehouse Cinemas relied on this judgement in constructing its case and by putting practices into place which would make the Forum adopt the semblance of a trade union. By meeting the narrow criteria of s1 of TULR(C)A the Forum was able to demonstrate it regulated the relations between workers and employers, even though it was compromised and subject to interference by the same employer. BECTU put forward that a trade union should be interpreted as stemming from Article 11 of ECHR in a broad and inclusive sense and that the narrow and contradictory interpretation of UK law was inadequate and superceded by the European judgement[23]. The CAC effectively accepted the contradiction within the law and the narrowness of its own judgement by invoking a domestic legal mechanism (Part VI of TUL(C)RA) as a remedy. However, it must be noted that this mechanism is risky and underused because the bargaining unit for the Staff Forum covers all the cinemas, whereas the application for BECTU recognition was only at Clapham Picturehouse. The threshold to be met is therefore increased dramatically and is in favour of the employer.

To conclude, trade union recognition is a crucial struggle for BECTU and its success will determine the union’s effectiveness for years to come. It is clear from these two examples that the fight for wages within the cinema sector strengthens the struggle for recognition and helps reduce the isolation of trade unionists in different cinemas and across different employers. In the Curzon example, voluntary recognition was gained on the basis of successful brand damage/capture and cross-sector organising. In the case of Picturehouse, a determined, hostile employer, prepared to play the long game (as evidenced in the Forum’s history) and more concerned with conceding to its workers than its ethical credentials, has been able to curb BECTU’s expansion effectively. However, the trade unionists have made it clear that this is merely the end of one chapter in the Ritzy workers’ struggle for the living wage and the Picturehouse workers’ struggle for trade union recognition. We owe them a debt of gratitude and they can bet their sweet or salty popcorn that come the next round, the rest of the cinema sector will be there in solidarity.

Bibliography:

Statute:

Paragraph 35 of Schedule A1 or TULCRA 1992 – collective agreements

Schedule VI of TULRA 1992 – derecognition

s178 (2) TULRA 1992 – collective bargaining

Article 11 of the European Convention on Human Rights

Cases and reports:

CAC – TUR1309/2003 BECTU & City Screen Limited

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140701192834/http:/www.cac.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=4676

CAC – TUR1/853/2013 BECTU & Curzon World

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140701192834/http:/www.cac.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=4676

CAC – TUR1/895(2014) BECTU & Picturehouse Cinemas Limited

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/404362/Acceptance_Decision.pdf

CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2001-2002 http://web.archive.org/web/20030405113735/http://www.certoffice.org/annualReport/pdf/2001-2002A.pdf

Demir and Baykara v Turkey [2008] ECHR 1345

R (on application of Boots Management Services Ltd) v CAC and ors [2014] EWHC 2930

Netjets Management Ltd v CAC [2012] IRLR 986

Journals and newspapers:

Julian Arato ‘Constitutional Transformation in the ECtHR: Strausbourg’s Expansive

Recourse to External Rules of International Law’ in BROOKLYN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, VOLUME 37, 2012, NUMBER 2

‘Curzon Cinemas to recognise BECTU’ 16 November 2013 https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2063

‘March with London’s cinema workers: Thurs 17 July’ 11 July 2014 https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2215

‘Living wage victory at Curzon cinemas’ 29 October 2014 https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2271

‘Support grows for recognition at Curzon Cinemas’ 6 August 2013 https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/1988

No “spirit of 45” for the workers at the liberal intelligentsia’s favourite cinemas by Rowenna Davis 2 April, 2013 http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2013/04/no-spirit-45-workers-liberal-intelligentsias-favourite-cinemas

APPENDIX A

Results of petition in support of union recognition for BECTU at Curzon World from CAC TUR1/853/(2013)

A The name of the relevant subsidiary company.

B The number of workers on the Employer’s list employed by each subsidiary company.

C The number of Union members employed in each relevant subsidiary company; and this number as a proportion of workers employed by that company.

D The number of petition signatories (irrespective of Union membership) of workers employed by the relevant subsidiary company; and this as a proportion of total workers employed by that company.

E The number of the signatories in column D that were Union members and this as a proportion of workers employed by the relevant subsidiary company.

F The number of the signatories in column D that were non-members and this as a proportion of workers employed by the relevant subsidiary company.

[1] A good example of this have been the pickets at the Amnesty International Football Film Festival and the Human Rights Film Festival held at Picturehouse Cinemas.

[2] Moreover, even in European law ‘the right to bargain collectively with the employer has, in principle, become one of the essential elements of the ‘right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of [one’s] interests’ set forth in Article 11 of the Convention.’ (a quote from the Demir and Baykara v Turkey [2008] ECHR 1345 judgement in BROOKLYN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, VOLUME 37, 2012, NUMBER 2)

[3] Schedule A1 – 1.1 of Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 and ERA 1999

[4] Section 10 of TULR(C)A 1992

[5] Section 11 of TULR(C)A 1992

[6] https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/1988 and http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2013/04/no-spirit-45-workers-liberal-intelligentsias-favourite-cinemas

[7] https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2063

[8]CAC – TUR1/853/2013 BECTU & Curzon World

[9] https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2215

[10] https://www.bectu.org.uk/news/2271

[11] TUR1/309(2003) BECTU & City Screen Limited

[12] TUR1/895(2014) BECTU & Picturehouse Cinemas Limited

[13] Demir and Baykara v Turkey [2008] ECHR 1345

[14] The Demir judgement is complex and most of its implications fall outside the scope of this essay. The case hinged on the right of Turkish municipal civil servants to organise collectively and the interpretation of Article 11 (freedom of assembly and association) of the European Convention of Human Rights.

[15] Incidentally, Mr Allenby was not available to attend the CAC hearing.

[16] Para 42, p17 of CAC – TUR1/895(2014) BECTU & Picturehouse Cinemas Limited

[17] p19 of CAC – TUR1/895(2014) BECTU & Picturehouse Cinemas Limited

[18] para46 , p19 TUR1/895(2014) BECTU & Picturehouse Cinemas Limited

[19] TULR(C)A 1992

[20] Para35 of Schedule A1 of TULR(C)A 1992

[21] R (on application of Boots Management Services Ltd) v CAC and ors [2014] EWHC 2930

[22] Independent trade unions such as Accord and Advance both started as staff associations, the former representing Santander workers and the latter representing HBOS workers, also in the banking sector. A review of Accord was asked for in 2001, but did not lead to a formal review after the Certification Officer undertook an informal investigation. (see CERTIFICATION OFFICE FOR TRADE UNIONS AND EMPLOYERS’ASSOCIATIONS Annual Report of the Certification Officer 2001-2002)

[23] The danger is that national courts will see Demir as a threat because ‘Demir & Baykara thus represents an assertion of competence to hold the Member States to norms they did not consent to, and cannot strictly control.’ (p357, BROOKLYN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, VOLUME 37, 2012, NUMBER 2)